My mother occasionally talked about her family, using the words, family ties, in a conversation. I seldom hear this term anymore, with families perhaps not as close as they were back in the day. I can’t say that about all because I believe ours is, for the most part.

Family ties refer to the strong connections and relationships that exist among members of a family. These bonds are often based on shared experiences, love, support, and a sense of belonging, which help keep family members united across generations and through life’s challenges.

Countries with the strongest family ties are often found in regions where extended families play a central role in daily life and cultural traditions. For example, nations in Southern Europe, such as Italy, Spain, and Greece, are well known for their close-knit family structures, with multiple generations living nearby and frequent family gatherings.

Similarly, many countries in Latin America, such as Mexico and Brazil, emphasize family loyalty and support, with strong intergenerational bonds remaining a cornerstone of social life.

In parts of Asia, including India, China, and the Philippines, family ties are also deeply valued, with respect for elders and communal decision-making being common practices.

These cultures often prioritize family obligations above individual pursuits, fostering a sense of unity and mutual support among relatives. The Western world, which includes the United States and Canada, appears to lack the same close family bonds as other regions.

My mother had four sisters. One of them, Opal, died in 1930 at age one. Cazaree was only 21 when she passed away from leukemia in 1948. The other two, Katrulia and Flavius, lived long, bountiful lives. Perhaps the death of Opal and Cazaree is why my mom and the other siblings remained so close.

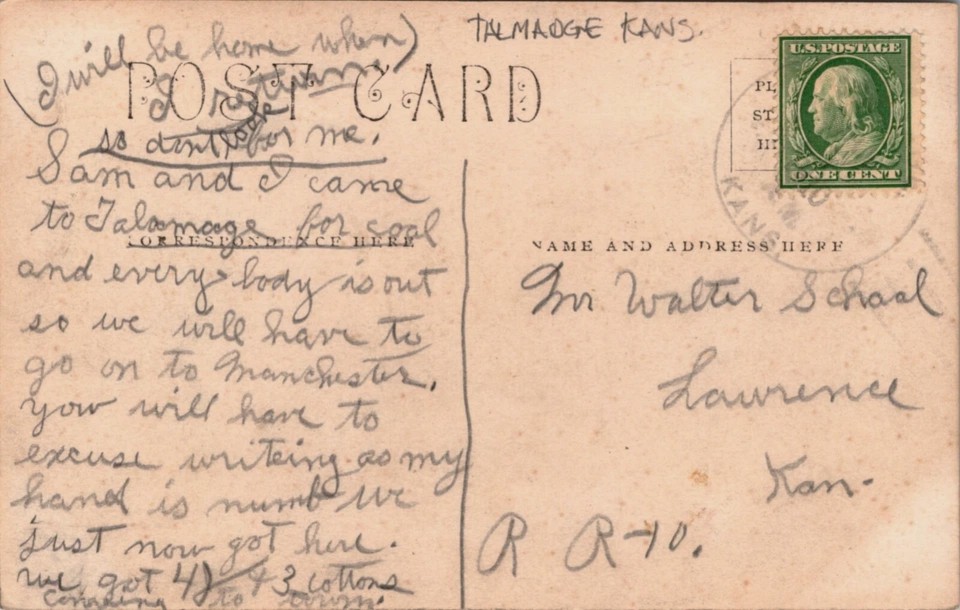

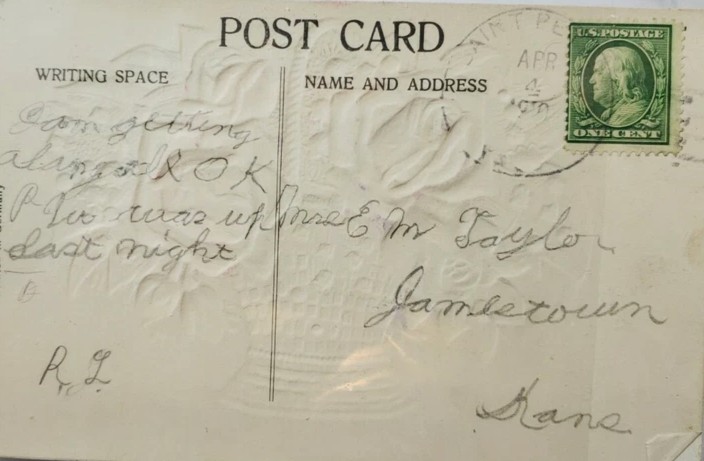

If they weren’t writing each other letters, they were sending postcards. In the 1960s through 1970s, long-distance phone calls from Alaska to Alabama could be expensive. Mom devised a way to let her sisters know that all was okay without spending a dime. She’d dial and let the other phone ring twice before hanging up.

As time went on, the phone rates went down. At this point, they’d talk to each other for hours. I don’t know what they found to yak about. Mom and her siblings had their disagreements, yet that never stopped them from communicating.

I suppose you could say that their family ties overrode any hostility. Mom believed in following the Bible verse, Ephesians 4:26. Simplified in my own words, this verse means, “Before the sun sets, let peace rise.” I especially like that verse because of the numbers alone. Only a few close friends will get the meaning here.

I always had good communication with my parents and brother after we went our separate ways. I try to talk to Jim at least once a month, if not more. We email, as I don’t text and never will. My fingers are too big to touch the right keys. Mom would be proud that our family ties, which she so expected, have not wavered.

I try to keep the same going with my two grown children and five grandchildren. It’s tough because they all have active lives, and we live too far away for weekly visits. I tune in to our grandson, Decker’s, hockey games when they’re live-streamed, always rooting for him and the Eden Prairie Eagles.

I’ve also watched several of the grandchildren’s school and church programs on the internet. Perhaps that separation in distance has made our family ties that much stronger, much like Mom and her sisters.

Hopefully, Gunnar and Kay, along with Miranda and Dennis, including grandchildren, Kevin, Grace, Decker, Reece, and Mykah, adhere to Ephesians 4:26 should conflict ever come between any of them. “Never let the sun go down without resolving a family conflict.”

Their departed grandmas, Bonnie and Tallulah, would wish the same!