For the past couple of months, I’ve been on intense writing projects involving old postcards. I’ve learned some history lessons from the pictures on front, while encountering funny and sadness from those people writing them, including the recipients.

It’s like being able to legally read someone’s mail, or eavesdrop on a personal phone call. I did that a few times as a kid when we had a party line. That form of entertainment came to a grinding stop when Mom caught me. She grabbed the phone and apologized to the person on the other end. My bottom was toasted soon afterwards.

This project has also allowed me to use psychological insight into how and why some of these cards were written. Some folks might ask after that last comment, “Do you have a background in psychology, Mr. Hankins?” The answer is no. I’m just an old man with an opinion. There’s a mess of us out there.

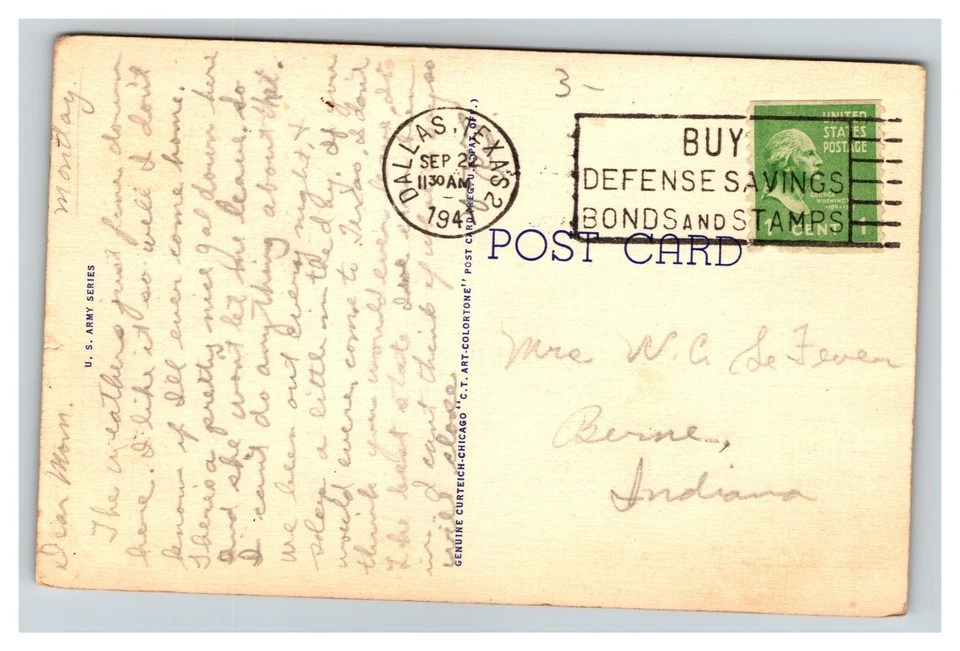

Before I go further, let me reveal things about my latest project. The card is postmarked from Dallas, Texas, September 22, 1941. Beside the circular stamp is another rectangular one marked, ‘Buy Defense Savings Bonds And Stamps.’ WWII hadn’t officially started, but tensions were high between the US and Japan.

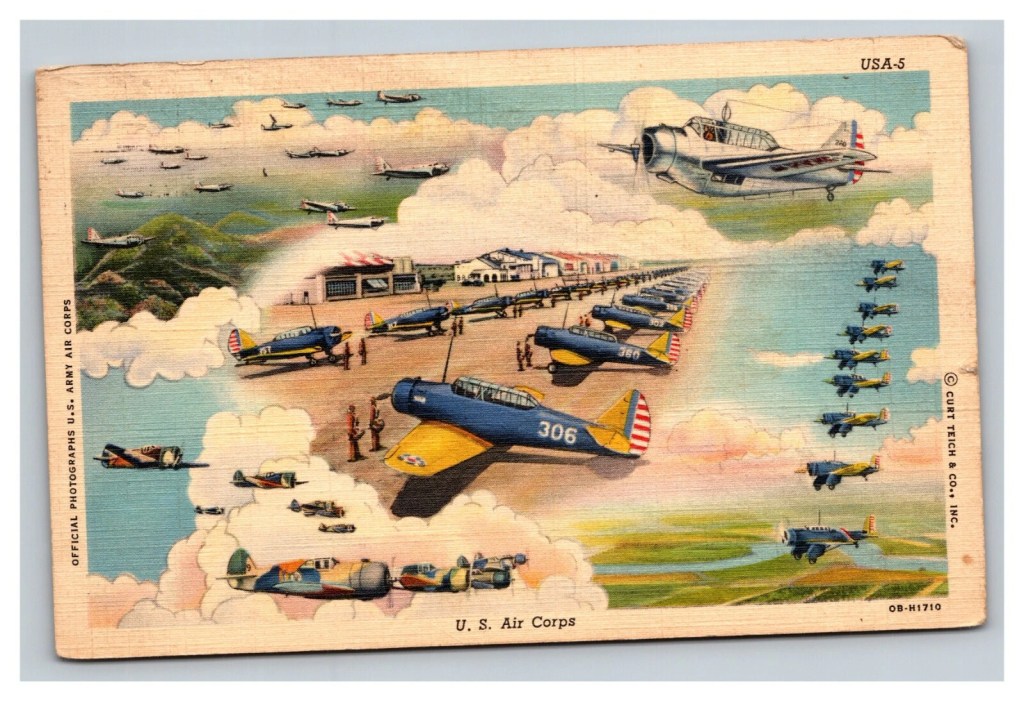

On the front of this lithographed postcard is a color picture showing training airplanes of the Army Air Corps. This branch of the military was called such before being renamed the United States Air Force in 1947. The recipient of the card is Mrs. W.C. Lefever in Berne, Indiana. The pencil-written message goes as follows, with typos and errors left unchanged:

“Dear Mom, Monday.

The weathers just fine down here. I like it so well that I don’t know if I’ll ever come home. Theres a pretty nice gal down here and she wont let me leave, so I can’t do anything about that. We been out every night + sleep a little during the day. If you would ever come to Texas, I don’t think you would ever leave. It’s the best state Ive ever been in. I cant think of what else to say so will close. Your son Robert”

I could just barely read the sign-off because the postmark covered it. There were enough readable letters to finally make things out. I’m sure Robert Arnold Lefever’s mom, Blanche, was tickled pink to get this message from her youngest boy.

William Clarence Lefever, Robert’s father, wasn’t mentioned in the correspondence, although both parents were still alive in 1941 and living together, as records indicate. The objective of the card and the way it was written is quite clear to me.

Robert was evidently having problems with his dad and saw this as a way to get back at the old man. What better way to say I love you than by letting both parents know that he was ‘sowing his wild oats’ and he’d never see them again.

Before the start of each Indianapolis 500 race, the late Jim Nabors sang, “Back Home Again in Indiana.” I believe the tradition is still being fulfilled by other singers. One or two word changes to the first four lines of this song can be made to reflect most anyone’s former home. For me, that would be switching Indiana for Alabama, Alaska, or Arizona.

“Back home in Indiana

And it seems that I can see

That gleaming candlelight is still shining bright

Through the sycamores for me.”

Research shows that Robert A. Lefever didn’t stay in Texas, eventually returning home to Indiana and marrying a local woman named Lillian in 1949. Robert’s buried in a Fort Wayne cemetery with his wife. Someone chose to spell their last name the old way on their gravestone, Lefevre.

Both parents, along with older brother Russell and his wife, Nora, are laid to rest 45 miles away in Berne. There’s no record of Robert serving his country during the war, yet there is a Russell Lever from Fort Wayne who was deployed and safely returned.

This research reminds me of Luke 15:11-32. This is the story of the prodigal son. A father has two sons. One is responsible, while the youngest is just the opposite. This immature boy asks his dad for his inheritance and then goes out and squanders it. After all of the money is gone from frivolous and foolish living, he comes crawling back home, expecting to live with the pigs.

Instead, his father puts on a big feast, which the older son finds to be a great disappointment. He can’t believe his father is doing this, for after all, he was the mature one. The older child is angered by this lavishness, yet goes along with things, while the father is delighted that his lost son is now returned.

Is that how Clarence Lefever saw things after Robert finished sowing his wild oats in Texas and came back home? I’d like to think so!