Old Tucson, located just west of Tucson, Arizona, is well known today as a movie studio and theme park. However, its history during World War II is less widely discussed.

Old Tucson was originally constructed in 1939 as a movie set for the film “Arizona,” starring William Holden and Jean Arthur. The set was built to resemble a western frontier town, and its authentic design quickly made it a popular location for film production. After the completion of the movie, the site remained intact and began to attract attention from both Hollywood and the local community.

When the United States entered World War II in late 1941, much of the nation’s resources and attention shifted toward the war effort. Tucson itself became a hub for military activity, with Davis-Monthan Air Force Base playing a critical role in flight training and aircraft operations.

Old Tucson, however, did not directly serve as a military installation or training ground during WWII. Instead, its primary use remained as a movie set. Hollywood productions slowed during the war years, but the site was maintained and occasionally used for film work when resources allowed. Some local residents visited the site, and it became a small tourist attraction, offering a glimpse of the Old West to servicemen on leave or stationed in the area.

The war years were marked by resource shortages and rationing, which affected all aspects of life, including movie production. Building materials, fuel, and manpower were prioritized for the war effort, limiting expansion or redevelopment of Old Tucson during this time. Nevertheless, the site’s existence helped sustain local interest in western heritage and provided a modest economic boost through tourism.

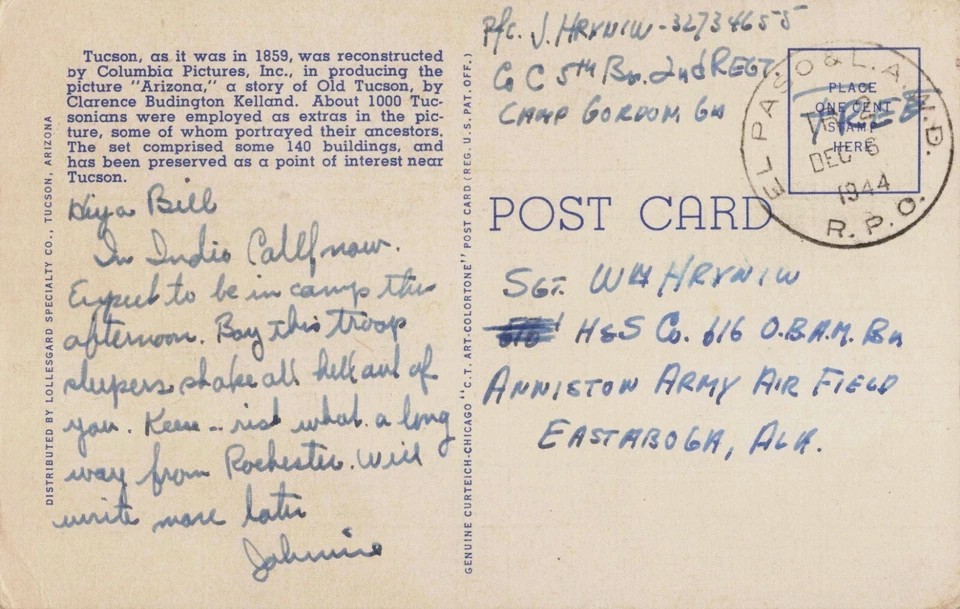

A 1944 picture postcard sent from Pfc. John Hryniw in Indio, California, to Sgt Wm. Hryniw at Anniston Army Airfield in Eastaboga, Alabama, shows a photo of Old Tucson as it looked in the successful western movie, “Arizona.” There’s much more to this postcard than a scene from a 1940s cowboy movie.

A message on the back of this card reads as follows:

“Hi ya Bill,

In Indio Calif now. Expect to be in camp this afternoon. Boy this troop slupers shake all hell out of you. Keee-rish what a long way from Rochester. Will write more later.

Johnnie”

John Hryniw and William Hryniw were brothers from Rochester, New York. Their parents, Peter and Anna, were immigrants from the Ukraine. Both young men had enlisted in the Army during WWII, with “Johnnie” sent to the Desert Training Center at Camp Young for duty.

I’m not sure what John meant by troop slupers, other than perhaps military slang for maneuvers, or supervisors. Marching and performing war games in the California, Nevada, and Arizona deserts was beyond brutal. Pfc. John Hryniw, along with thousands of others, endured the horrible elements with a good many dying. John’s brother, William Hryniw, on the other hand, had things much better in Alabama.

General George Patton had the following to say about soldiers training in the desert, “The California desert can kill quicker than the enemy. We will lose a lot of men from the heat, but training will save hundreds of lives when we get into combat.”

PBS did a documentary on Patton’s Desert Training Center, and I’ve enclosed a short portion on what they reported:

“Indeed, during maneuvers away from camp, men lost their lives in the heat, with locals in Yuma and Phoenix registering protests over the training conditions.

Few of the troops had ever experienced the dry climate, and they struggled to acclimate to temperatures upwards of 120 degrees and brutal sandstorms. Salt tablets were distributed to the men in hopes they would prevent dehydration and cramping, but water was rationed.

Sometimes, particularly early on or while out on maneuvers, troops received only one canteen of water per day, with an erroneous understanding that one could be trained to survive on less water and that such deprivation prepared them for the harsh conditions they would face in North Africa.

Men learned to keep cool without much shade and to avoid the natural dangers of the desert like rattlesnakes and scorpions. The testing of equipment proved equally important and led to practice in desert camouflage, better maintenance of tanks and other vehicles, and even new supplies like dust respirators.

To prepare bodies for long hours and hard work, all troops were required to run a 10-minute mile within a month after their arrival, an activity that not only acclimated them to the desert but also hardened their bodies and minds for the challenges that lay ahead.

This “seasoning” of the men proved an important goal; while abroad, troops sometimes faced desolate locations, cut off from supplies or even water, lacking shade and the comforts of home.

Even as the Desert Training Center shifted to broader training operations after fighting in North Africa ended, officers celebrated the hardening of men as crucial preparation for the difficult conditions faced in Europe and the Pacific. That the landscape varied, with valleys, rocky foothills, and mountain ranges, served as an additional bonus; troops could prepare for diverse battle terrains.

The vast expanse of land provided enough room for multiple battalions to train in situ, to create living spaces from the ground up, and experience maneuvers that mimicked actual warfare. Engineers outlined camp roads, signal corpsmen laid telephone lines, and army air corpsmen took advantage of year-round clear skies to obtain crucial flying skills and practice. Thus, troops gained actual practice in the roles they would hold abroad in a landscape and climate similar to what they would encounter.

They did so in their units, which bonded the men together, particularly because of the isolation and new experiences they shared. Difficult conditions provided confidence to men who worked through them; even the days without sleep and hundred-mile marches provided a taste of what was to come.

Patton’s early emphasis was on constant movement; not only did this train the men for actual combat situations, but made it more difficult for the enemy to find and destroy a camp as well. Thus, while the Desert Training Center held about 14 divisional camps, much of the training happened beyond their borders in the raw desert landscape.”

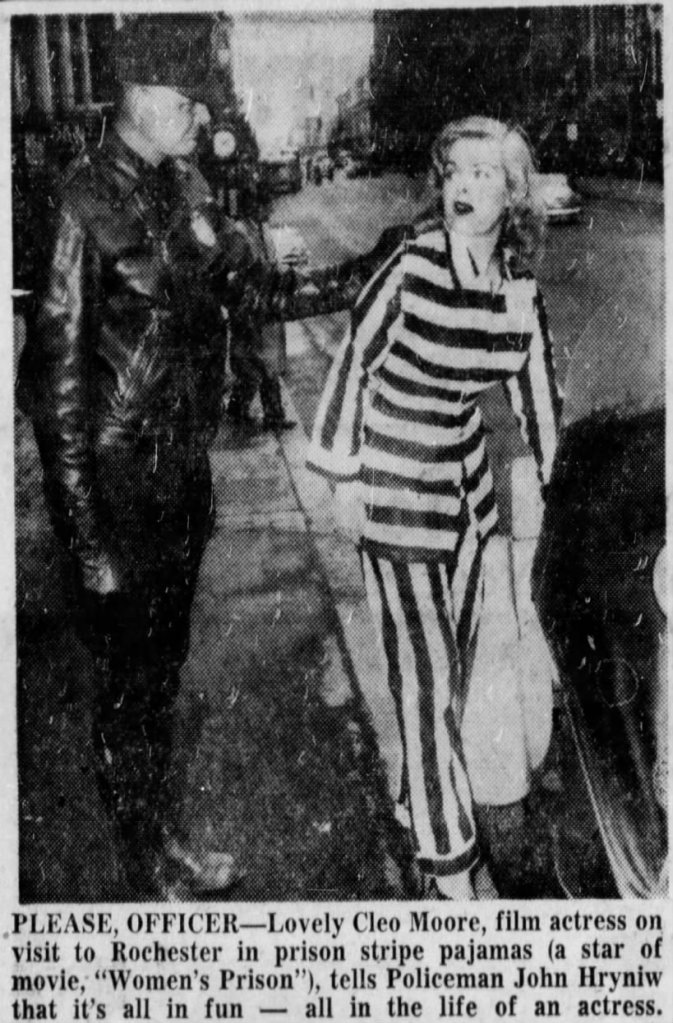

After the war, Pfc. John Hryniw became a policeman in Rochester, with newspaper accounts telling about some of his exploits dealing with criminals. There’s no doubt that the desert training toughened him up for this type of work.

Patrolman Hryniw spent time as a motorcycle cop—even surviving a crash when an evidently inebriated driver ran into his Harley-Davidson, knocking him off the bike. Injured as he was, John was still able to arrest the fellow and send him to jail.

For the latter part of his police career, John Hryniw became a detective before retiring, moving to Oregon with his wife, and then spending time as an auctioneer. John died on May 16, 2014, at the age of 92.

William Hryniw found a much safer and profitable occupation after leaving the service. He was a successful insurance agent and property manager, remaining in New York after retiring. William “Bill” Hryniw passed away at 83 on September 7, 2002.

The California and Arizona deserts are still littered with remnants of General George Patton’s desert training. I’ve found my share while out poking around. Old Tucson survives as well, although it’s seldom used for movies anymore.