Dunlap, Kansas, is a small, unincorporated community with a rich history marked by its role in post-Civil War migration and its unique place in the story of African American settlement in the Midwest. Located in Morris County, Dunlap’s legacy is intertwined with the Exoduster movement and the settlement of freed individuals seeking new opportunities after emancipation.

Dunlap was founded in the late 19th century, named after Joseph G. Dunlap, an early settler and entrepreneur who played a significant role in the community’s establishment. The area was originally part of the Great Plains, inhabited by various Native American tribes, including the Kansa and Osage, before white settlement began in the region.

The arrival of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway in the 1870s spurred more rapid development. The railway provided crucial access to markets and transportation, encouraging settlement and economic growth in the area.

One of the most significant chapters in Dunlap’s history began in the late 1870s and early 1880s with the influx of African American settlers known as “Exodusters.” Fleeing racial violence and economic hardship in the post-Reconstruction South, many Black families migrated to Kansas, inspired by its reputation as a free state and the legacy of abolitionist John Brown.

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a prominent African American leader and former slave, played a pivotal role in encouraging this migration. He and others led groups of Exodusters to settle in Dunlap and surrounding Morris County, establishing one of the most significant Black farming communities in Kansas. These settlers built homes, churches, schools, and businesses, creating a thriving and resilient community despite facing significant social and economic challenges.

By the 1880s, Dunlap had become a vibrant town with a diverse population. The African American settlers established their own churches, including the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church, and built schools such as the Dunlap Colored School, which provided education for Black children in the community.

The town supported several businesses, farms, and social organizations. Despite segregation and discrimination, the Exoduster community in Dunlap achieved a degree of self-sufficiency and prosperity, contributing to the broader story of Black migration and settlement in the American Midwest.

Dunlap’s fortunes began to decline in the early 20th century. Economic hardships, including the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, led many residents to leave in search of better opportunities elsewhere. The consolidation of rural schools and the decline of the railroad also contributed to the town’s dwindling population.

By the mid-20th century, Dunlap had largely ceased to function as a distinct town, and many of its historic buildings were lost or fell into disrepair. However, the legacy of the Exodusters and their descendants remains an important part of the region’s history. Efforts to preserve and commemorate Dunlap’s past continue through historical societies, reunions, and educational initiatives.

Today, Dunlap is an unincorporated community, a ghost town, with only a few remaining residents and structures. The nearby cemeteries, such as the Dunlap Cemetery and the St. Paul AME Cemetery, serve as reminders of the town’s unique heritage and the enduring legacy of the African American pioneers who once called it home.

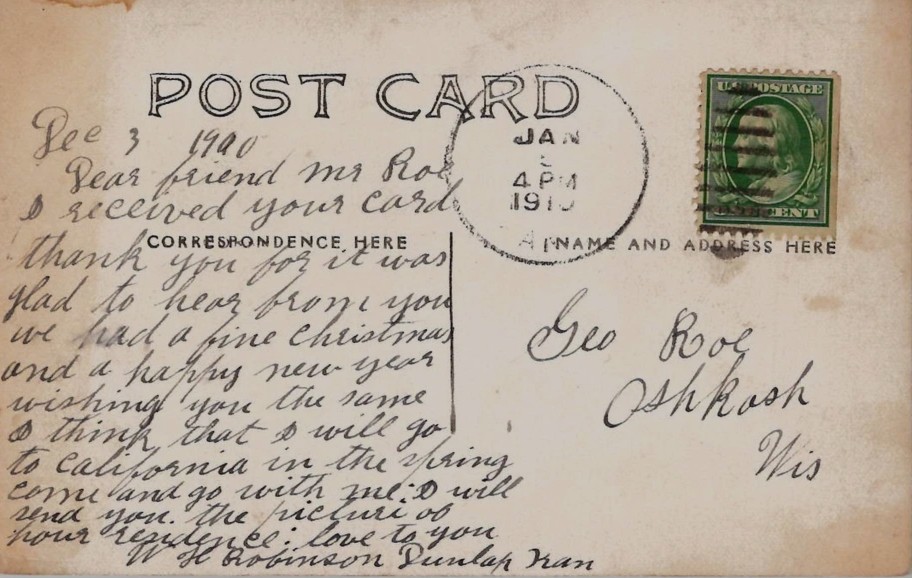

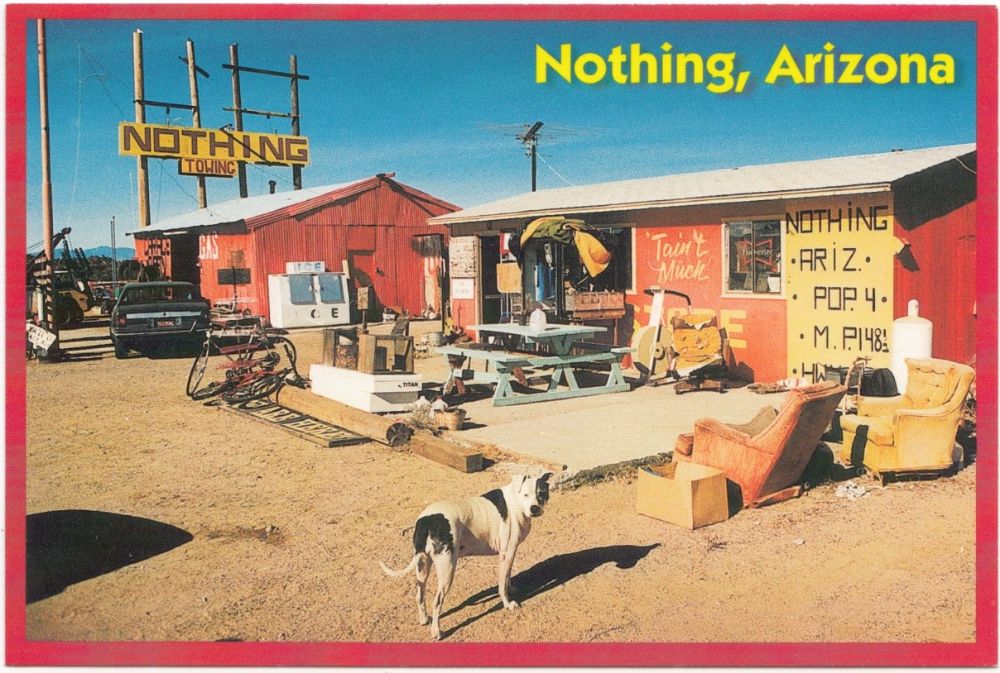

A picture postcard mailed from Dunlap, on January 3, 1910, has a photograph of the residence of W.H. Robinson. This card was sent to his friend, George Roe, in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. A nicely written message, transcribed as written, says:

“Dec 3 1900

Dear friend Mr. Roe

I received your card. thank you for it was glad to hear from you. we had a fine Christmas and a happy new year. wishing you the same. I think that I will go to California in the spring. come and go with me: I will send you the picture of our residence: love to you

W.H. Robinson Dunlap Kan“

Mr. Robinson was somewhat confused, as the card was mailed in January, although it was supposedly written in December. He also corrected the date from 1900 to 1910.

William H. Robinson was born in Ohio in 1844. He married around 1885 to a woman from Illinois named Mary. The couple had two children, Arthur and Sarah. William was a farmer and horticulturist.

William and Mary moved to Long Beach, California, in 1919. William H. Robinson passed away in 1924, while his wife died in 1936.

George Roe, the postcard recipient, was born in England on November 22, 1882. He was a woodworker by trade, owning a small shop in Oshkosh. George married wife, Lydia, around 1917. They had three children, Evelyn, Rexford, and Lydia. George died in 1959, with Lydia passing away in 1983 at the age of 97.

Unlike the Robinsons, who moved to California from Kansas, the Roes stayed put in Wisconsin. Both are buried in the small city of Omro.