The story of early Kansas one-room school teachers is a vital chapter in the development of education across the American Midwest. These educators, often working in isolated and challenging environments, played a crucial role in shaping generations of students and helping to build strong, resilient communities. Their dedication and adaptability laid the foundation for modern education in Kansas and beyond.

In the mid-19th century, as settlers streamed into Kansas, communities quickly recognized the need for accessible education. With limited resources and sparse populations, the one-room schoolhouse became the most practical solution.

These small structures were typically built by local families and served children of all ages, often from as far as several miles away. The teacher was not only an educator but also a central figure in community life.

Early Kansas school teachers were predominantly women, many of whom were young and unmarried. Teaching was one of the few respectable professions available to women at the time, offering an opportunity for independence and personal growth. Male teachers were less common but often taught in larger communities or advanced subjects.

Teachers faced rigorous expectations. They were responsible for instructing students in a variety of subjects, including reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history. Their days began early, as they often had to clean the schoolhouse, start the fire, and prepare the space before students arrived. In addition to teaching, they managed disciplinary matters, organized community events, and sometimes even cared for sick children.

Life as a one-room school teacher in Kansas was demanding. The pay was meager, and teachers often boarded with local families or lived in modest accommodations nearby. Transportation was limited, so teachers walked long distances or rode horses to reach their schools. Winters could be harsh, and keeping the schoolhouse warm was an ongoing challenge.

The school year was typically organized around the agricultural calendar. Children were often required to help with planting and harvesting, so attendance fluctuated according to the season. Teachers adapted lessons to meet the needs of students who ranged widely in age and ability, providing personalized instruction and fostering a close-knit learning environment.

Most early Kansas teachers received minimal formal training. Some had attended teacher institutes or normal schools, but many relied on their own education and the support of community members. Certification requirements varied, but teachers were often evaluated by local school boards through examinations and classroom observations.

The influence of one-room school teachers extended far beyond academics. They were leaders, role models, and often advocates for community improvement. Schoolhouses doubled as meeting places for church services, social gatherings, and town meetings. Through their work, teachers helped instill values of perseverance, civic responsibility, and lifelong learning.

By the early 20th century, Kansas began to consolidate its rural schools, gradually replacing one-room schoolhouses with larger, centralized institutions. The legacy of the early one-room school teachers, however, remains embedded in Kansas history. Their commitment to education and community continues to inspire educators today.

Early Kansas one-room school teachers were pioneers in every sense of the word. They overcame adversity, educated generations of children, and helped build the character of rural communities. Their stories remind us of the enduring power of education and the profound influence dedicated teachers can have on society.

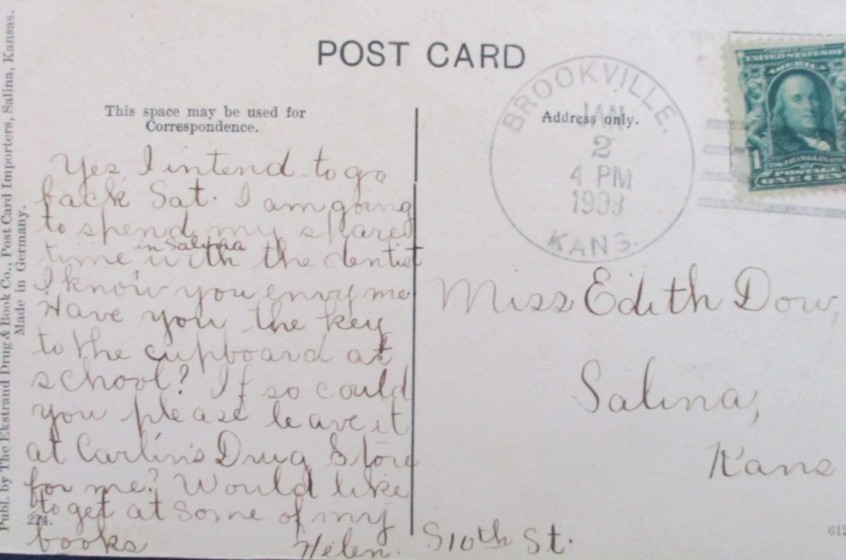

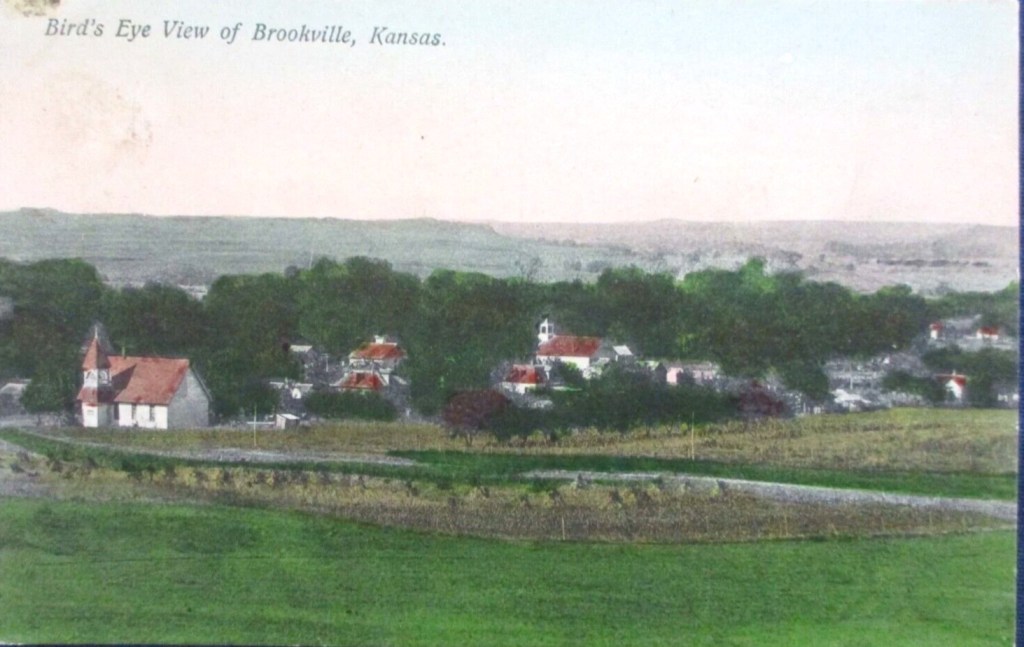

Edith Dow and Helen Rollman taught in one-room schools. They could be called ‘schoolmarms’ in a positive sense of this definition. A picture postcard that Helen sent Edith from Brookville, Kansas, on January 2, 1908, is job-related, along with being personal.

The two women were close friends, as newspaper articles indicate. The front of the card shows a street in Brookville. Helen’s message on the back reads as follows:

“Yes, I intend to go back Sat. I am going to spend my spare time in Salina in the dentist. I know you envy me. Have you the key to the cupboard at school? If so could you please leave it at Carlin’s Drug Store for me? Would like to get at some of my books. Helen”

Miss Edith W. Dow was born April 29, 1887, at Salina. Kansas, to parents, Ezra and Florence. She was a graduate of Salina High School, Class of 1905. Edith lived all her life in Salina except for 25 years spent teaching in Boulder, Colorado.

Before moving to Colorado, she taught for two years at Assaria and five years at Salina. Miss Dow studied at Emporia State University, Colorado University, and the University of Northern Colorado. During all of this time, she never married.

Edith Walker Dow died November 7, 1981, at Presbyterian Manor in Salina. She was a member of the First Presbyterian Church, the P.E.O. Sisterhood, Delta Kappa Gamma, National and State Retired Teachers Associations, Saline County Historical Society, and Daughters of the American Revolution.

Born in 1888, the card sender, Helen K. Rollman, came from a family with educational ties. Her father, Professor Thilon J. Rollman, had been a teacher before becoming Superintendent of Brookville Schools. He was also the town treasurer of Brookville. One of six children, Helen followed in Professor Thilon’s footsteps.

Miss Rollman graduated from Kansas State Teachers’ College, with her teaching beginning in 1914 at Salina, Brookville, Quincy, and Polk public schools. Like Edith Dow, she never married. Helen retired in 1953, and she passed away on May 15, 1980, in Topeka, at the age of 92.