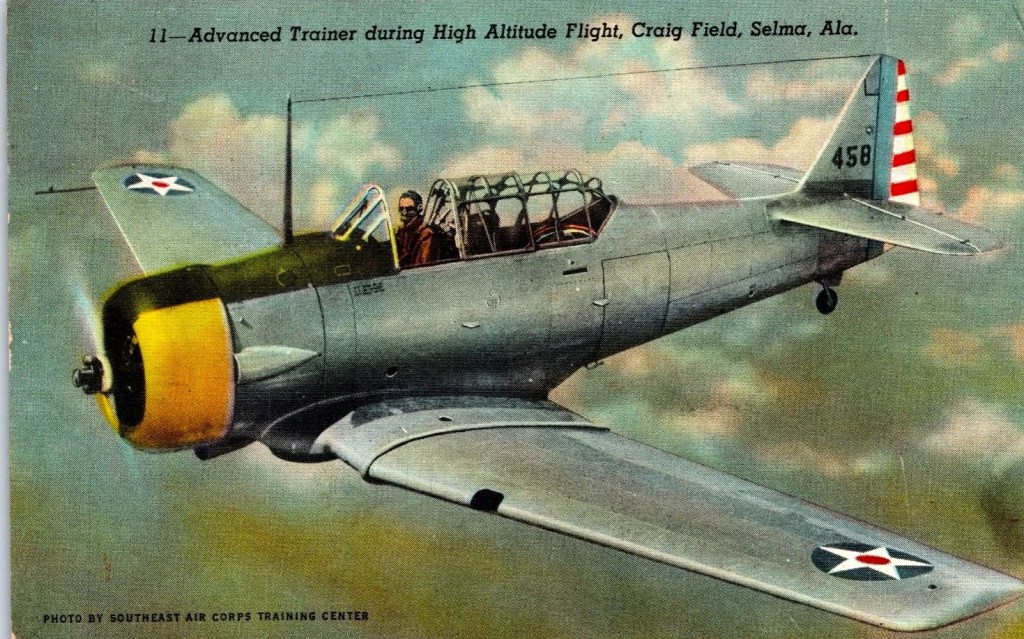

A picture postcard showing an Army Air Corps training airplane on the front was sent to Miss Sue Howard of Mt. Vernon, Illinois, on September 16, 1942. The sender was Private Anthony “Tony” J. Infantino, who was at the base during this time. Infantino’s postcard has a Selma postmark. His message to Sue was a polite and cordial one.

“Stopped here and will soon be on our way to Texas by plane. Will write later. Your pal, Tony”

Craig Field, located near Selma, Alabama, was a significant military airfield during World War II. Established as part of the United States’ rapid expansion of air training facilities, Craig Field played a vital role in preparing pilots for combat and supporting the broader war effort. This overview explores the history, operations, and legacy of Craig Field during the WWII era.

The base was constructed in 1940 as the threat of global conflict grew and the United States recognized the need to train a vast number of aviators. Named in honor of Lieutenant Bruce K. Craig, a military aviator who lost his life in service, the field became operational in early 1941. Its primary mission was to serve as an advanced pilot training base under the Army Air Forces’ Southeast Training Center.

During WWII, Craig Field was primarily dedicated to advanced flight training. Cadets, having completed basic flight instruction elsewhere, arrived at Craig for rigorous, comprehensive training on advanced aircraft.

The base specialized in transitioning pilots to operate single-engine fighter planes and multi-engine bombers, crucial to the Allied air campaign. Training included instrument flying, formation maneuvers, navigation, and aerial combat tactics.

Thousands of American and Allied pilot trainees passed through Craig Field during the war. The influx of personnel brought economic growth and increased activity to the surrounding Selma community. The base employed both military and civilian workers, fostering a sense of shared purpose in the national war effort.

Craig Field operated a variety of aircraft, including the North American AT-6 Texan, which was widely used for advanced pilot training. The field was equipped with modern runways, hangars, and support facilities, reflecting the technological advancements of the era. The curriculum emphasized proficiency in the latest aviation technology and combat readiness.

The pilots trained at Craig Field went on to serve in every theater of World War II, flying missions over Europe, the Pacific, and North Africa. The field’s rigorous training programs ensured that aviators were well-prepared for the challenges they would face in combat. Craig Field thus played a pivotal role in the overall success of the U.S. Army Air Forces during the war.

With the end of WWII, Craig Field continued to serve as a training and operational base, adapting to the needs of the emerging U.S. Air Force. Its contributions during WWII are remembered as a key chapter in the history of American military aviation, and the field’s legacy endures in both the region and the broader context of air power development.

Craig Field’s history during World War II is marked by its critical function as a center for advanced pilot training, technological innovation, and community involvement. Its legacy reflects the determination and teamwork that underpinned the Allied victory in the air war.

At Craig Field for a brief time, Pvt. Anthony Infantino was probably on his way to Randolph Field near San Antonio for further training. He was born on July 22, 1919, in New York. Enlisting in the Army at the age of 23, tragically, Tony was killed in action (KIA) while parachuting into enemy territory in the Netherlands.

This happened on March 24, 1945, with his remains not brought back to the States until 1948, where it was interred in his hometown of Pawling, New York. Flags were lowered to half staff, with quite a few residents turning out for the service. Tony’s young friend may have never known.

Sue Howard was much younger than Tony, and judging by the context of the postcard message, their relationship was strictly one of friendship. Perhaps she was more of a pen pal than anything. Citizens were encouraged to write the soldiers for encouragement and to lift their spirits. This nationwide campaign was called V-MAIL, or Victory Mail.

Miss Betty Sue Howard married Eugene L. Delves on March 27, 1954. The couple stayed together until their deaths. Eugene passed away in 2011, and Betty Sue, seven years later, in 2018.