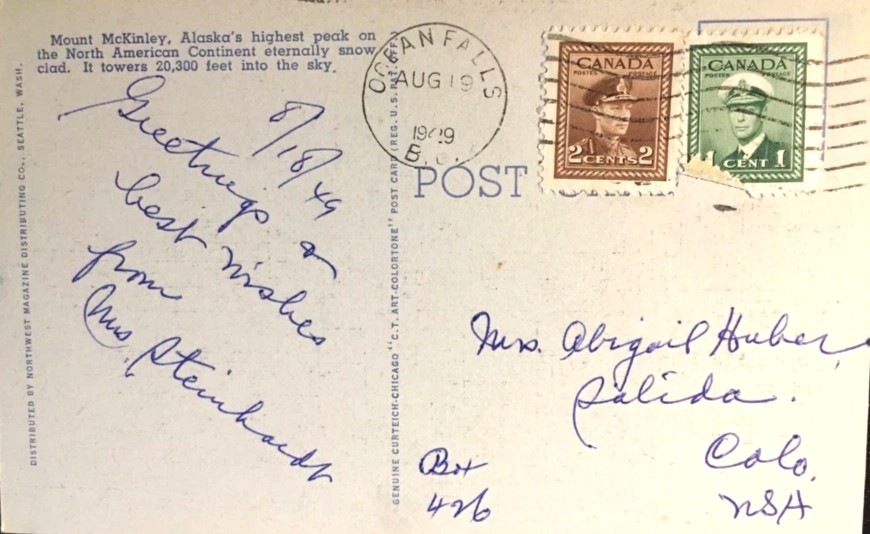

On July 4, 1911, 114 years ago, someone named Lula wrote a simple yet somewhat complex message on a black and white picture postcard of the Wrangell Narrows. It was mailed from Hoonah, Alaska, four days later, on July 8. The brief note says,

“7/4/11

I wonder where you are to-day. Thinking of the good time we had last year makes me want to be there too. Geo. & the children are shooting crackers on the beach. This picture is a scene on the way up to Hoonah & Juneau. Lula”

I can only assume that Lula was referring to a Fourth of July celebration she had celebrated with Mrs. John F. Good, the previous year. What the lady meant by George and the kids shooting crackers is somewhat puzzling, although I believe I have finally figured things out.

No, the family wasn’t lining up Nabisco saltine crackers on the beach and plinking them with a .22 rifle, this before hungry seagulls swooped down and inhaled the remnants. Lula was merely talking about shooting off firecrackers. Unfortunately, they didn’t have bottle rockets as well.

Why she was going to Hoonah and Juneau after passing through the Wrangell Narrows is a mystery in itself. Was she going fishing for tuna in Hoonah and Juneau? The most plausible explanation is that the woman was on a steamer taking a cruise.

Lula was undoubtedly glad to get out of Dodge (South English, Iowa). That statement didn’t come along until Marshall Matt Dillon and Miss Kitty made it popular on “Gunsmoke,” but it works just fine here.

Before I tell you who Lula and Mrs. John F. Good were, South English, Iowa, Wrangell Narrows, and Hoonah, Alaska, have to be briefly explored first.

South English, Iowa, is a small farming community named after the nearby English River. In 1910, its population was just 338 residents, reflecting its rural character and close-knit atmosphere. Located in southeastern Iowa, the town is surrounded by fertile farmland and has traditionally relied on agriculture as its economic foundation. Life in South English was marked by a strong sense of community and the rhythms of the farming calendar, making it a quintessential example of early 20th-century rural Iowa.

Wrangell Narrows is a scenic and essential waterway located in Southeast Alaska, known for its narrow channel, strong currents, and importance to both local communities and marine traffic. This passage has served as a lifeline for the region’s transportation, commerce, and culture.

This body of water stretches approximately 22 miles (35 kilometers) between the towns of Petersburg and Wrangell, Alaska. It lies between Mitkof Island to the east and Kupreanof Island to the west, forming part of the Inside Passage—a network of protected waterways renowned for safe navigation and stunning scenery.

The narrows are well-known for their winding curves and variable widths, at some points narrowing to less than 300 feet across. Depths also fluctuate, requiring careful navigation, especially for larger vessels.

Wrangell Narrows is famous among mariners for its complex navigation. The channel is dotted with more than 60 navigational aids—buoys and markers—that help vessels avoid shallow areas, rocks, and other hazards. Currents can be strong and tidal shifts significant, making timing and skill essential for safe passage.

Large cruise ships typically avoid Wrangell Narrows due to its tight bends and shallow spots, but ferries, fishing boats, and freight vessels frequently traverse the waterway, connecting regional communities and supporting the local economy.

The towns of Petersburg and Wrangell depend on the Narrows for their connection to the rest of Southeast Alaska. The Alaska Marine Highway ferry system and other local vessels use the passage regularly, making it a crucial route for passengers, goods, and services.

The Narrows is surrounded by lush temperate rainforest, home to Sitka spruce, western hemlock, and abundant wildlife. Visitors may see bald eagles, harbor seals, sea lions, and even humpback whales in the surrounding waters. The shoreline is dotted with small islands, tidal flats, and forested hills, offering breathtaking views for travelers and photographers.

While Wrangell Narrows is not typically navigated by large cruise ships, its scenic beauty and accessibility make it a favorite for smaller expedition vessels, private yachts, and kayakers. Petersburg, often called “Little Norway” due to its Norwegian heritage, and Wrangell, one of Alaska’s oldest towns, are both popular stops for visitors exploring the Inside Passage.

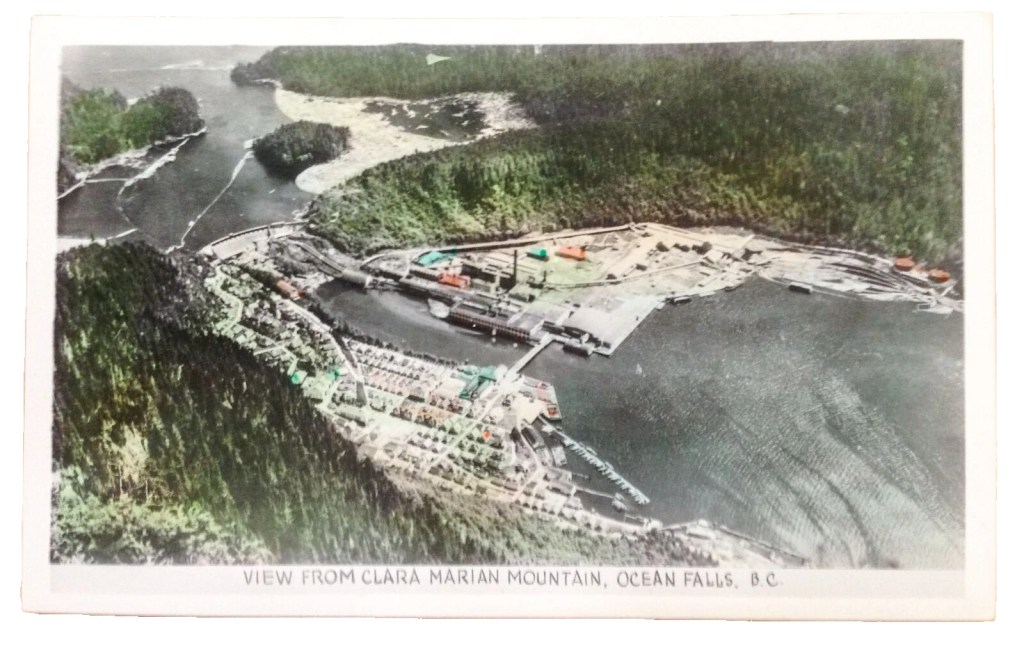

Hoonah, Alaska, is a small city located on Chichagof Island in the Alexander Archipelago of Southeast Alaska. Its history is deeply rooted in the traditions of the Tlingit people, who have inhabited the area for thousands of years. Originally a seasonal camp for fishing and gathering, Hoonah became a permanent settlement as Tlingit families established more substantial homes and communities.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Hoonah saw increased interaction with non-Native settlers, missionaries, and traders, which influenced its development. The town was officially incorporated in 1946, but its cultural heritage remains strong, with many residents tracing their ancestry directly to the region’s original Tlingit inhabitants.

Hoonah’s economy has traditionally relied on fishing, logging, and subsistence activities, though tourism has grown in recent years, particularly following the development of cruise ship facilities at Icy Strait Point. Today, Hoonah preserves its unique blend of traditional culture, natural beauty, and community resilience, making it an important hub in Southeast Alaska. For those still wondering, there are no tuna in Hoonah.

Mrs. John F. Good is actually Mrs. Ida Parnell-Good. She married John on July 24, 1895, becoming his second wife. John’s first spouse, Hannah, died in 1892 after 18 years of marriage. Ida Good was born in 1857 and passed away 80 years later in 1933. They were farmers.

It took some time-consuming sleuthing to uncover Lula’s history, as she also went by the name Lulu. Born on April 18, 1866, to Merritt and Margaret Brown, Lula married Jacob Doll on February 17, 1887. When Jacob died four years later in 1891, she wed George Franklin Marshall. This took place on October 2, 1892. Between both marriages, the couple had eight children.

Lula Belle Brown-Doll-Marshall passed away at the age of 59 on February 12, 1924. The Marshalls, like the Goods, listed farming as their sole occupation. Both families were quite well-to-do in their endeavors, with this allowing for George, Lula, and four of their children to make the Alaska trip.

John F. and Ida Parnell-Good are buried at English River Church of the Brethren Cemetery in South English, Iowa, while Lula Belle and George Marshall are interred at Keota Cemetery in Keokuk County.